DARK SIREN

Matica Hrvatska Gallery

Zagreb, Croatia, 2023.

Installation

Dark Siren The senses of a middle-aged observer are saturated with a visual, intoxicating, and seductive barrage of impenetrable information layers, more specifically, an audio-verbal-optical cacophony. It seems we live in an era of iconolatry, the worship of the holy image of capital. In this high-tech illusionistic, ludicrously beautiful world of the entertainment industry, multimedia, and surrogate beauty, and yet increasingly unjust world, the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer. This is fertile ground for visible extreme ideologies, power plays, war, and the radicalization of the world, alongside the current ecological and a potential energy crisis. Behind it all lies an unfair distribution of capital. The negative utopia is here; we live it, though in the stark reality of everyday life, we're not aware of it. The future has already passed, where were you?

Martina Miholić has been exploring the cold markers of dystopia in a hybrid conglomerate composed of high and low culture determinants, which here includes a mythological dimension, through the total world of art materialized in spatial visual constructs for some time. Dark Siren is a metaphor that contains mythic and the author's contemporary connotations of open symbolization and works. The siren was originally a sea monster with the head and chest of a woman and the lower body of a bird with feathers (body and tail), and only later, in the Middle Ages, became the fish that is archetypally ingrained in our memory through popular culture. Until the 7th century BC, sirens were depicted solely as birds with human heads, possibly under Egyptian influence. Etymology, according to some interpreters, means the one who entangles, binds with a magical song. This brings to mind the familiar image of Odysseus tied to the mast and sailors with wax in their ears. Odysseus resisted the seductive song of the sirens, even though he heard their song. On an archaic Greek vase from the 5th century BC (British Museum, London), a siren is depicted in ancient illusionism as having thrown herself to death, distressed like the Sphinx when her riddle was discovered. Thus, sirens symbolize the danger of sailing but also denote death.

Despite many negative aspects, on some sarcophagi, they mark the deities on the Isle of the Blessed who enchant the blessed with their music. However, and to this, the contemporary version by Martina also refers, sirens symbolize deadly seduction. Figuratively speaking, if life, like the interpretation of ancient heroes, is considered a significant journey, sirens represent traps arising from desire, longing, and passion of unconscious night energies of dream and the instinct of self-destruction.

In this sense, the artist's Dark Siren is a contemporary femme fatale of the dream industry that functions in numerous incarnations beyond the cruel realities of everyday life, pointing to (un)concealed sexuality as a form of destructive power of instinct and the mysterious and dark power of the realm of fantasies. The downfall of such unrealistic imaginations, male projections about women (and women about men, though that is not discussed here), are reflected in magical literary and film images like Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958), Verhoeven's Basic Instinct (1992), Bruckner's Icy Moon (1981) which Polanski adapted into Bitter Moon (1992), or De Palma's Femme Fatale (2002), as well as numerous dreamy Lynchian versions. The most outlined is the male projection of Scottie (James Stewart) in Vertigo when he finally sees Madeline/Judy (Kim Novak) in a magical frame, dressed and made up according to his illusion of a double - the previous, but identical woman he believes to be dead - who ultimately ends tragically like a negative anima. We project onto the opposite sex those sexual desires we already deeply carry within us. According to Žižek, the problem is not whether our desires are satisfied or not. The problem is how to know what we desire. There's nothing spontaneous or natural in human desires. Our desires are artificial; we must be taught to desire. Therefore, film is the ultimate perverse art. It doesn't give you what you desire but tells you how to desire.

In this regard, the embodiment of the artist's fatal siren, which she imaginatively and symbolically visualizes in space with a plexiglass container filled with dark liquid and a print on foil into which a photograph of a female body is inserted, suggests the arousal and evocation of the figure of the dark siren. The projection of threatening femininity is materialized within a dystopian environment but with hints of camp aesthetics possessing a perversely sophisticated allure. Martina even uses a kind of trash elements.

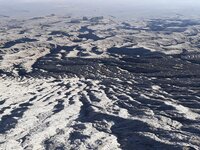

With all mentioned and more, the author stretches across an entire gallery, creating a multi-perspective spatial ambiance with a series of multidimensional and meaningful spatial constructs and objects. The space is an open field of the image. By her unconscious, Martina probes, projecting this into a cooled dystopian vision. Negative utopias are realized in coordinates, for example, from Kafka to Villeneuve. These are classic dystopias in which the individual is mechanized and woven into a cold, inhuman system of futurization made of inhumane automation, SF, and retro-virtualization. They are still present today and imaginable as everything that is abandoned, emptied of life, architecturally and industrially displaced, which becomes a post-industrial outline of emptiness as indicated by the author's orthogonal projection drawings, as well as the negative dystopian environment suggested by a photograph of a volcano and creations of black trees and crystallized animal bones. With the entire construct, Martina achieves a kind of analog metaverse in which the observer exists as part of optimization. The reach of the function of the author's work reflects its potentially uncomfortable reaction. By embodying the mythic in the virtual, Martina Miholić has realized a post-humanist vision in which the dawn of the fatal woman is reflected in cooled object and spatial visualizations. But remember, every dystopia was initially a utopia, like the mirror screen of the computer in front of which these lines were written, as well as the gold rush of the internet and new technologies that surge from all sides, like the hologram of the dark siren.

Paula Bučar Željko Marciuš

Reflecting on the paradox of contemporary triumph of aesthetics through the lens of beauty, Michaud observes: "It's crazy how beautiful the world is. Packaged products are beautiful, expensive clothes with their stylized logos, bodies buffed up or rejuvenated by plastic surgery, made-up faces [...]. Even dead bodies are beautiful—neatly multiplied in plastic covers and lined up in front of ambulances. If that's not beautiful, then it must be beautiful. Beauty reigns. [...] it has become imperative. Be beautiful or at least spare us your ugliness. [...] Depending on societies, religions, modes of production, this world could be felt, lived, or perceived as a valley of tears, a world of suffering or pleasure, effort or comfort, justice or disgrace, earthly humility or aspiration beyond—never as beautiful or ugly. [...] We, the civilized people of the 21st century, live in times of the triumph of aesthetics, the worship of beauty—in times of its idolatry. It is difficult and even impossible to escape the empire of aesthetics. It seems that even the moral judgment on behavior is there for the sake of 'creating beauty,' and morality becomes aesthetics and cosmetics of behavior. The world must be full of beauty, and suddenly it is overwhelmed with beauty."; Y. Michaud, Art in a Gaseous State: An Essay on the Triumph of Aesthetics, Naklada Ljevak, Zagreb, 2004, pp. 1-2.

Consider numerous variations of the fairy tale from its creator H.C. Andersen to Disney. Under the influence of Egypt, which depicted the souls of the deceased in the form of a bird with a human head, it was believed that a mermaid was the soul of the deceased who [...] transformed into a human vampire. See: J. Chevalier, A. Gheerbrant, Dictionary of Symbols, Cultural Information Center; Jesenski and Turk, Zagreb, 2007, p. 656. Also compare: J. Pinsent, Greek Mythology, Otokar Keršovani, Opatija, 1990, p. 137.

The same.

Consider, for example, Eco's comparative tables on the history of male beauty from antiquity onwards, such as the Naked and Clothed Adonis to, for instance, the face and hair of Adonis. From popular culture, there are Marlon Brando (Julius Caesar), but also Arnold Schwarzenegger (Commando), James Dean, David Bowie, George Clooney… The history of female beauty is comparative, but we have already sufficiently exploited it in the text. See: Umberto Eco, The History of Beauty, HENA COM, Zagreb, 2004, pp. 19-27.

For instance, compare Eco's comparative tables on the history of male beauty from antiquity to the present, such as the Naked and Clothed Adonis up to, for example, the face and hair of Adonis. From popular culture, there are Marlon Brando (Julius Caesar), but also Arnold Schwarzenegger (Commando), James Dean, David Bowie, George Clooney... There's also a comparative history of female beauty, but we have already sufficiently explored it in the text. See: Umberto Eco, History of Beauty, HENA COM, Zagreb, 2004, pp. 19-27.